Missing – presumed taken prisoner.

As I write these notes, I have beside me the most momentous piece of paper I have ever received. For me it is profound in the extreme. It unlocks a door which has been firmly closed to me and my family for ninety years.

It is the reply, from the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva, to my request for information regarding my father, who was a prisoner of the Germans in the first World War. I made my application to the ICRC, via the Internet, as the result of a conversation I had with Eric Dalgleish, over the refreshments after our Group’s A.G.M. last December (2007). He told me the story of his own son’s research into his grandfather’s time as a prisoner in World War I (see page 12 of Issue 70 of Kith & Kin “The result of cleaning out a cupboard”.)

Inspired by Eric’s story, I sent my request to the ICRC on 2nd January 2008. I knew from Eric that their reply could take up to three months to arrive. Just one week less than the three months, it came – I had requested that it should be sent by post. I had been searching for this information for over twenty years and now, here it was in my hand.

I had been brought up, from my earliest remembered days, with the knowledge that my father had been a prisoner of war, but that was all, there were no details. The family would not discuss this time and I knew that I must not ask my father as he did not wish to be reminded. After his death in 1981, I tried all the avenues I could think of to find out more. I started at Kew - then the P.R.O.- but his war record was not there. Eventually the “Burnt Records” became available; his was not there either. I did, however, obtain a copy of the medal roll showing his regiment, number and a list of the battalions in which he had served. This told me that he had been in the 1/4th battalion of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment, when taken prisoner. I then contacted the regimental museum in Lancaster Castle, but the only information they could offer was the date and place of his repatriation.

As a child, in my home town, my mother had shown me the Drill Hall where my father had enlisted on September 12th 1915, in the Prince of Wales’ South Lancashire Regiment, the “Pals”. The hall is still there, the street leading to it is actually called Volunteer Street. I found out, from a book lent to me by Graham Gare, that my father’s battalion, the 12th, had been absorbed into the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment in March 1916, and had gone to France in June 1916, I presume in readiness for the Somme – July 1916.

On another of our Group’s visits to Kew, I consulted the regimental war diaries. These are wonderfully detailed accounts of the day to day activities of the battalions, written in goodness knows what difficult circumstances by, I guess, an appointed officer. They are written in pencil, often in the most beautiful handwriting. My father was an “other rank”, so I did not expect to find out much and I did not know where or when to look. This search, although fascinating, yielded nothing significant.

One of my sons – they were all helping me with my research – came across a book written just after the war by the Commanding Officer of the Regiment. He bought this for me – it is an original copy which arrived neatly packed in its, also original, brown paper wrapper. I treasure it for its detail and the fact that in the Appendix at the back there are lists of those killed, wounded, missing and taken prisoner. In the latter list is my father’s name. Until I saw it there, I had seen no official list on which he appeared.

I consulted the films of local newspapers in my home town library. During the war they published weekly lists of casualties. Again, I didn’t know when to look for his capture and found nothing. I even wrote to the German authorities (with the assistance of my German sister-in-law), knowing how well their records had been documented, but received a polite reply telling me that the relevant records had been destroyed by bombing in the Second World War!

In the year 2000, a television documentary called “Prisoners of the Kaiser” was shown. Again, the book of this film was bought for me. It is a harrowing account of the privations endured by POW’s and emphasised to me what my father and those with him had gone through. This book is full of pictures but again, I could not relate to any of them because I did not know what or where I was looking for.

Now, since the arrival of this special letter from Geneva, all is changed. It tells me first, formally, my father’s name, date of birth, regiment, regimental number, battalion and company. All of this confirms that we have the right person. It then goes on to disclose the vital information for which I had so long searched. My father was taken prisoner on 20th November 1917 at Guillemont, during the battle of Cambrai. He was then taken to the camp Munster II and later transferred to the camp at Friedrichsfeld. Remarkably, he arrived in Dover on 28th November 1918 on his way home, only seventeen days after the Armistice was signed. I think that, at this point, he must have been fortunate and for that I am thankful.

Having all this relevant information has enabled us to go forward into much more detailed research. Google Maps shows the exact battle location; the” History of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment,” referred to earlier, and now reprinted, is invaluable, as are the regimental war diaries, copies of which we have been able to obtain from the regimental museum in Lancaster. These tell, in minute detail, the events of the battle as it progressed, after commencing at 6.20am on 20th November 1917. We can see where “A” company – my father’s – was positioned and how they fared; at first advancing, later having to retreat and ultimately being cut off and captured. We have learned of the huge losses on that day and marvel that we, the next three generations, are here at all.

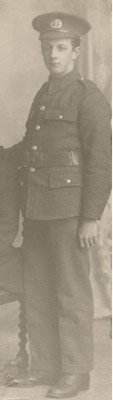

My ICRC letter gives another date – 17/01/1918 – stating that this is the date of the list from which they derived their information. That makes me wonder if my father’s family, here in England, knew nothing of his whereabouts from the time when he would have been reported missing, one of eighty such, after the battle on 17/11/1917, until they heard that he had been taken prisoner after the release of this information in January 1918. What must my grandparents, uncles and aunt have endured during the uncertainty and dread and, maybe, hope of those eight or more weeks? They never told me; and my mother, what would have been her position in all this? I have no idea where their relationship stood when my father went to war, but on this photo of him, taken in 1915, I think that I can make out a ring on the third finger of his left hand and that must surely signify something. I know that ring, I have it now.

I hope that my success with this research might inspire those of you who have reached a full stop in yours, to keep on. First World War prisoner information in this country is negligible. Geneva is your only hope and it is now very accessible on http://www.icrc.org/eng/contact-archives so do it! If I can be of any help to anyone, just ask. Incidentally, as my father’s next of kin, I paid not a penny for the facts which, to us, are truly priceless.

Joyce Latham